Greg Gregory, PhD | Executive VP, Partner

Dan Danielson, MS, R.Ph. | Senior Director, Access Experience Team

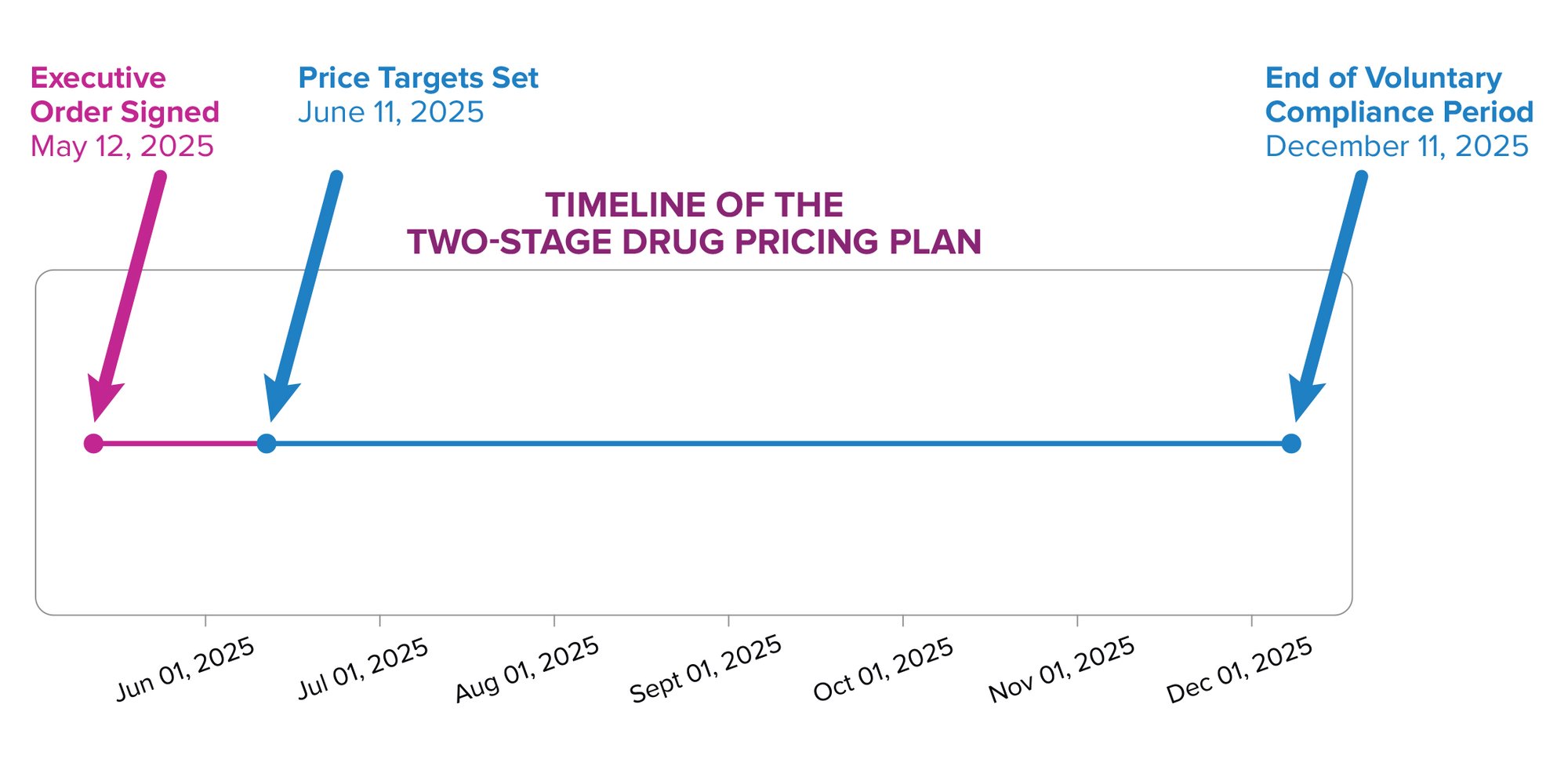

The Executive Order signed by President Trump on May 12 outlines the administration’s two-stage plan to implement drug price controls in the United States.

The first stage directs the U.S. Trade Representative and the Department of Commerce to give drug makers price goals based on the lowest costs paid among similarly developed nations, within 30 days (on or around June 11, 2025). The administration has subsequently noted: “The MFN target price is the lowest price in an OECD country with a GDP per capita of at least 60 percent of the U.S. GDP per capita.” During the next six-month period, drug manufacturers are expected to make significant progress in lowering their prices. If sufficient progress is not made, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is to develop a new rule that ties U.S. prices to the lowest price paid by other developed countries.

So, What Happens Next?

Global Price Referencing and Launch Strategy:

Introducing drug price controls tied to prices in other countries could signal a shift in how the U.S. regulates pharmaceutical pricing—effectively outsourcing domestic pricing policy to foreign governments. Since many ex-U.S. prices are a function of local cost-effectiveness analyses, budget constraints, and negotiated agreements that don’t reflect the U.S. market environment, this creates a misalignment. Drug companies may question the logic of anchoring U.S. prices to systems with different priorities, values, and healthcare structures.

One downstream effect: pharmaceutical companies may delay or forgo launches in lower-priced markets if those prices are used to benchmark U.S. pricing. This could create global access inequities, where patients in some countries may lose early access to breakthrough therapies due to the ripple effect of U.S. pricing strategy. This is already a documented dynamic in global launch sequencing. Meanwhile, drug makers are lobbying European policymakers to offset these dynamics, warning that U.S. price referencing could accelerate their operational shift away from Europe.

Fiduciary Responsibility

While this may seem like an esoteric issue, it has immense impacts on everyday Americans—particularly those who are retired or planning to retire. The first part of the plan relies on drug manufacturers “voluntarily” reducing their prices to match those in other countries. Many of these companies are publicly traded or backed by venture capital firms and must determine their fiduciary responsibility to shareholders (such as 401(k) plans and other investors). From the manufacturers’ perspective, they may feel that they not only should not—but legally cannot—voluntarily reduce U.S. prices without a formal mandate, as doing so could conflict with their obligation to maximize shareholder value. This could expose them to shareholder lawsuits. As a result, despite the optics, drug makers may wait until HHS issues binding rules before taking action.

An exception to this perspective could exist with the few manufacturers structured as Public Benefit Corporations (PBCs). PBCs are legally permitted—and in some cases expected—to balance profit motives with social good, potentially allowing them to consider voluntary price reductions under certain circumstances.

What Will You Pay?

Instituting price controls of any kind will have a hugely disruptive effect on the economics of the U.S. healthcare environment. The real issue is: who are the winners and who are the losers?

Some consumers may indeed see reductions in out-of-pocket spending—most likely those who pay a fixed percentage of drug costs (coinsurance), as opposed to those who pay fixed dollar amounts (copays).

Medical practices could see a marked reduction in reimbursements due to price controls. Drugs administered in physician offices or clinics are often tied to an Average Sales Price (ASP). These drugs are typically reimbursed based on the ASP plus a percentage to cover carrying costs and provide a small margin. A reduced ASP leads to lower reimbursement and slimmer margins, negatively impacting the viability of physician practices—especially in rural and underserved areas.

As gross-to-net dynamics shift, insurers and PBMs may restructure benefit designs, formulary placement, or prior authorization policies in ways that blunt the intended consumer impact of price controls. Without rebate flexibility, PBMs may push for access fees or favor drugs with limited competition, potentially reducing therapeutic choice.

Stymied Research and Development?

Instituting price controls in the U.S. does not guarantee that prices in other countries will rise—or rise enough—to make up for the revenues lost in the U.S. Among other things, reduced revenues mean fewer funds available for the research and development needed to commercialize new drugs—not just in America, but globally. Without investments in basic science to discover new drugs and the resources to prove their safety, efficacy, and potential new uses, the development of new therapies is likely to slow significantly.

Administrative Complexity & Legal Challenges

Even if HHS moves forward with formal rulemaking, implementing a Most Favored Nation (MFN) policy will be complex. Determining reference countries, validating accurate and current pricing data across markets, and accounting for confidential rebates will create significant administrative burdens. Legal challenges and constitutional arguments around price-setting authority are almost guaranteed to follow.

As the healthcare landscape shifts under the weight of new policy and pricing pressures, strategic insight is more critical than ever. Discover how Precision’s Commercial Consulting team can help you navigate these changes and position your brand for success: Explore our Research & Strategy services.